⚠️ Every post begins with a question and grows from my ongoing search to know God and understand His purpose for humanity. What you read here reflects my current view—born from study and wonder—and I often revisit and update my writings as I continue to learn and see more clearly.

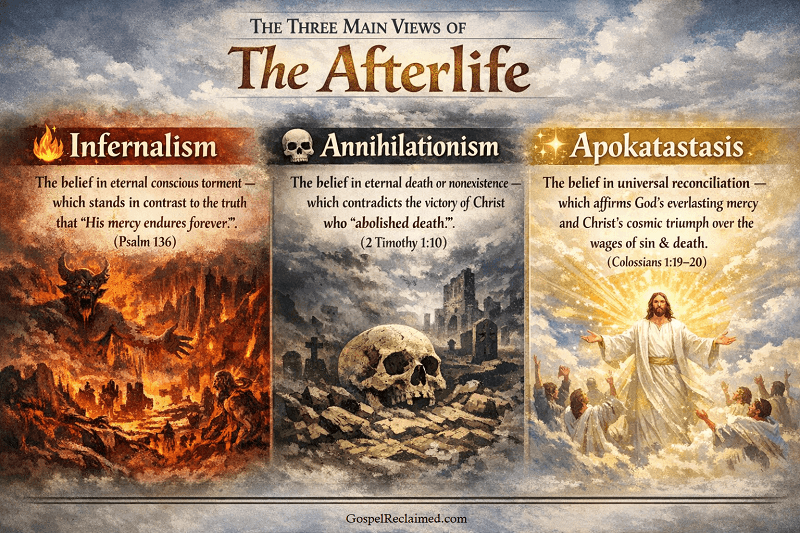

Let’s explore the three major views on the afterlife held by early Church Fathers:

- Infernalism (eternal torment in hell),

- Annihilationism (eventual destruction),

- Universal Restoration (ultimate reconciliation of all).

These perspectives shaped centuries of Christian thought and reflect how early believers wrestled with the nature of God’s justice, mercy, and purpose for creation.

In this post, we’ll unpack each view, examine the historical and philosophical roots of Infernalism—including its overlap with certain pagan ideas—and explain how it rose to prominence.

We’ll also highlight why Universal Restoration offers a compelling alternative rooted in the character of Christ. And at the end, you’ll find a simple comparison table to help keep the different views clear.

Infernalism: Eternal BBQ, Pagan Style

Welcome to Infernalism—the doctrine of eternal hellfire, where the unrepentant are said to receive a one-way ticket to endless conscious torment.

According to this view, championed by heavy-hitters like Tertullian and Augustine, sinners spend forever in a fiery abyss, wailing and gnashing their teeth while divine justice rolls on without end.

Now here’s where things get interesting: Infernalism bears a striking resemblance to ancient pagan concepts. Think Tartarus—the Greek underworld where enemies of the gods were banished for eternal punishment. Or the underworlds of Mesopotamian and Egyptian mythology, filled with imaginative forms of torment for the wicked.

In a world soaked in Greco-Roman thought, it’s no surprise that early Christian thinkers might have absorbed a few of these spicy cultural ingredients into their theology.

So why did Infernalism become so dominant?

Simple: it’s intense. It delivers drama, fear, and an urgent call to repentance—all things that made it very appealing to early church leaders.

By the time Augustine’s City of God hit the shelves, Infernalism had become the theological mainstream. It was effective, and fear, as history shows, is a powerful motivator.

But wait—didn’t Jesus talk about hell more than anything else? Actually… no. Not even close.

If you want to explore the original biblical words translated as “hell,” see Hell — The Real Story.

Annihilationism: The Cosmic Delete Button

Next up: Annihilationism—the view that says instead of roasting forever, the wicked simply cease to exist.

Advocated by early thinkers like Irenaeus and Justin Martyr (on their less fiery days), this perspective holds that the unrepentant aren’t eternally tortured, but ultimately “poof”—gone. No unending torment, no cosmic do-over. Just a final judgment, and then… lights out.

Annihilationism’s appeal lies in its moral coherence. The idea of eternal torture is hard to reconcile with a loving God, but the concept of a “merciful death” or end… that’s a little easier to digest.

It draws from verses like Psalm 37:20, where “the wicked vanish like smoke,” and avoids the mythological baggage that Infernalism sometimes carries.

So why didn’t this view catch fire (pun intended)?

Well, “Repent or be no more” doesn’t have the same dramatic punch as “Repent or burn forever.”

It lacks the fear factor that fueled revival tents and firebrand preaching. And for some, divine justice just didn’t feel satisfying unless the wicked really felt it.

Universal Restoration: Cosmic Group Hug

Finally, we arrive at Universal Restoration—arguably the most hopeful view of them all.

Championed by Church Fathers like Origen and Gregory of Nyssa, this perspective teaches that everyone will ultimately be saved. Hell, in this view, isn’t eternal punishment but a temporary, purifying process—a kind of spiritual rehab rather than a final sentence. [Foot note 👉 1]

In other words, God’s love doesn’t give up. It reaches even the hardest hearts—yes, even the guy who invented decaf—and transforms them over time. Think of it as the theological equivalent of “everyone eventually makes it home.”

Universal Restoration leans on the belief that God’s mercy triumphs over judgment (James 2:13), and that divine justice is about making things right, not punish; it is restorative, not retributive.

Origen, with his rich use of allegory, suggested that “hell” symbolizes a corrective process, a divine time-out meant to lead the soul back to God. It’s a beautiful vision of redemptive love.

But not everyone was comfortable with it. As the Church became more aligned with imperial authority, the idea of eventual salvation for all—heretics, pagans, and all—was seen as too generous.

Universalism was eventually labeled heresy at the Council of Constantinople. Still, Universal Restoration remains the profound expression of the belief that in the end, love really does win.

Why Infernalism Won the Popularity Contest

So how did Infernalism—with its intense, punishment-heavy theology—rise to the top among afterlife views?

1. It had powerful emotional appeal.

Fear is a strong motivator, and Infernalism delivered vivid, unforgettable imagery: lakes of fire, gnawing worms, and endless weeping. It made for gripping sermons and kept people tuned in.

Compared to that, Annihilationism felt underwhelming, and Universal Restoration sounded almost too hopeful to be true. Infernalism struck a compelling balance between warning and control—useful for a Church focused on preserving order and obedience.

2. It resonated with the culture of the time.

The Greco-Roman world was no stranger to the idea of “divine justice” as a public spectacle—gladiator games, crucifixions, and mythologies full of gods dishing out cosmic payback. Infernalism felt familiar, like a spiritual continuation of cultural expectations, dressed in Christian language.

With thinkers like Augustine introducing doctrines like original sin, the idea that humanity deserved eternal punishment took root and spread fast.

3. It supported institutional power.

Infernalism conveniently raised the stakes of belief and obedience. If the alternative to orthodoxy was eternal torment, people were far less likely to wander.

Compared to it, Annihilationism and Universal Restoration lowered the urgency. After all, if the worst-case scenario is vanishing—or being restored eventually—there’s not as much fear to fuel control.

Infernalism, with its high-stakes consequence, gave the institutional Church a persuasive tool to keep people aligned.

👉 But what if this fear-based doctrine is not just a distortion—but the most evil idea ever imposed on the Gospel?

Read my article: Hell – The Most Evil Doctrine of All Time to uncover how mistranslation, pagan myth, and power-hungry institutions turned Good News into eternal terror.

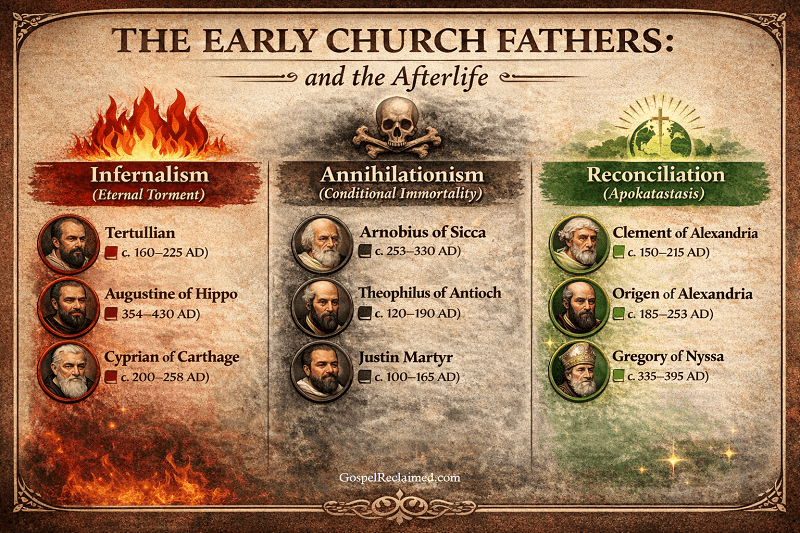

The Church Fathers: Who’s Team What?

To help keep things clear, here’s an outlining the key figures, the time periods they lived in, and which view of the afterlife they most strongly supported.

🔥Infernalism (Hell – Eternal Torment)

1. Tertullian (c. 160–225 AD) – Taught explicitly on the eternal conscious torment of the wicked. 📝 Apology, On the Soul, Against Marcion

2. Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD) – Cemented infernalism as dominant in the Western Church.

📝 The City of God

3. Cyprian of Carthage (c. 200–258 AD) – Spoke of fiery judgment and eternal separation.

📝 Epistles, On the Lapsed

💀Annihilationism (Conditional Immortality)

1. Arnobius of Sicca (c. 253–330 AD) – Argued that the soul is not inherently immortal. – God gives immortality to the righteous, and the wicked are destroyed.

📝 Against the Pagans (Book 2)

2. Theophilus of Antioch (c. 120–190 AD) – Wrote that humans were created mortal and only gain immortality through obedience.

📝 To Autolycus

3. Justin Martyr (c. 100–165 AD) – Though not a full annihilationist, taught conditional immortality. – Said souls of the wicked will ultimately perish.

📝 Dialogue with Trypho

✨Reconciliation (Apokatastasis)

1. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 AD) – Taught that God’s punishments were medicinal, aimed at restoring the soul. – Believed all rational beings would eventually be reconciled to God.

📝 Stromata, Miscellanies

2. Origen of Alexandria (c. 185–253 AD) – Developed the most detailed early doctrine of Apokatastasis. – Believed that even the devil and his angels could eventually be restored.

📝 On First Principles

3. Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335–395 AD) – Explicitly taught the eventual restoration of all things and all people.

📝 The Great Catechism, On the Soul and Resurrection

Note: some Church Fathers weren’t always crystal clear or consistent, so these placements reflect their most dominant theological leanings.

As for Augustine—arguably the most influential voice shaping Western Christian thought on the afterlife—his defense of Infernalism became so foundational that questioning it has, for centuries, risked raising theological eyebrows (or worse) before you even finish your sentence. 💀

The Takeaway

The theological tug-of-war among the Church Fathers left us with three major views of the afterlife: Infernalism with its fiery judgment, Annihilationism with its final fade-out, and Universal Restoration—a vision of ultimate reconciliation and healing.

Infernalism may have taken the spotlight, but not because it was the most biblical or theologically sound. It rose to dominance because it delivered high-stakes fear and reinforced institutional control—a dramatic narrative that fit the times.

✨ As for me? I stand with Universal Restoration. It’s the only vision where Jesus truly wins, not just over sin, but over every soul. Where grace doesn’t trickle, it floods.

Because if God’s love isn’t big enough to reach everyone…

If grace isn’t more abundant than sin…

If Jesus is called the Savior of the world, but somehow doesn’t save the world…

Then what exactly is the Good News?

Theology—you’re a wild ride. But when love leads, the journey is worth it.

FAQs

What are the afterlife theories?

The afterlife theories of the early Church Fathers: Infernalism (aka HELL), Annihilationism, and Universal Restoration.

What is the annihilation doctrine?

No eternal torment, no cosmic redo, just a swift “you’re done” and a fade to black.

What does universal reconciliation mean?

It’s the only doctrine where Jesus is the ultimate victor, not just over sin but over every soul, where grace doesn’t just trickle, it floods.

- My own conviction is that “hell” refers to the individual and collective consequences of millennia of sin as they are experienced within this present age. It belongs to the realm of the flesh and to the conditions of life under distortion. When the flesh dies, “hell” is left behind, and the soul encounters Love itself—free from all lies and deceit.

The function of this reality is pedagogical rather than punitive. In reaping what we sow, we are instructed in what is right, just, and pleasing—namely, the character of God that humanity forgot when it chose to live as though alienated from the divine life already present within us. I explore this theme more fully in my article ‘Missing the Mark‘.

What, then, occurs at death? I understand it this way: while humanity has been redeemed and objectively constituted as the righteousness of God in Christ at the level of the spirit, the soul—encompassing character, memory (both light and dark), relational fracture, trauma, and distorted perception of self, others, and God—undergoes purification and restoration so as to be brought into full correspondence with the blameless and holy spirit.

As to the duration of this restorative process, the question ultimately dissolves. Time belongs to this created order and does not govern the eschatological life of God, in which restoration is measured not by sequence but by completion. ↩︎