⚠️ Every post begins with a question and grows from my ongoing search to know God and understand His purpose for humanity. What you read here reflects my current view—born from study and wonder—and I often revisit and update my writings as I continue to learn and see more clearly.

What happens when everything you thought you knew about hell turns out to be wrong?

I know—that’s a loaded question.

Maybe you’re already thinking, “Oh great, another heretic trying to erase judgment and turn God into a cosmic teddy bear.”

I get it. Honestly? I once thought the same thing.

But here’s the truth: This isn’t about sugarcoating anything. It’s about facing the most honest and necessary questions a person can ask: If the Gospel is truly Good News, if Jesus is the Savior of the world, and if God is truly the person of Love… then how could endless torment ever fit into that story?

To ask these questions isn’t heresy. It’s the search for truth. And when you see it, I think you’ll realize something stunning: The Good News is even better than you were ever told.

So if you’ve got questions about hell—if something deep inside you has wondered, “Could God really be that mean? Or is there something more going on here?”, then you’re exactly where you’re supposed to be.

Let’s take a journey through history, through Biblical context, through the very heart of God and let’s see where the fire actually leads.

Lost in Translation: How “Hell” Was Born

Before we can understand what hell is (or isn’t), we have to face a simple, uncomfortable truth: most of what Christians believe about hell didn’t come from the Bible at all, but from paganism, philosophy, dualism, and mistranslation.

The English word hell comes from the Old English hel or helle, rooted in Germanic mythology, named after the Norse goddess Hel, ruler of the underworld. It was never a biblical concept, yet it eventually slipped into Christian vocabulary and replaced the original Hebrew and Greek terms and concepts.

Layered on top of that, Greco-Roman philosophies, pagan afterlife imagery, and later Latin mistranslations helped shape a picture of “hell” that no ancient Hebrew ever believed and that Jesus never taught.

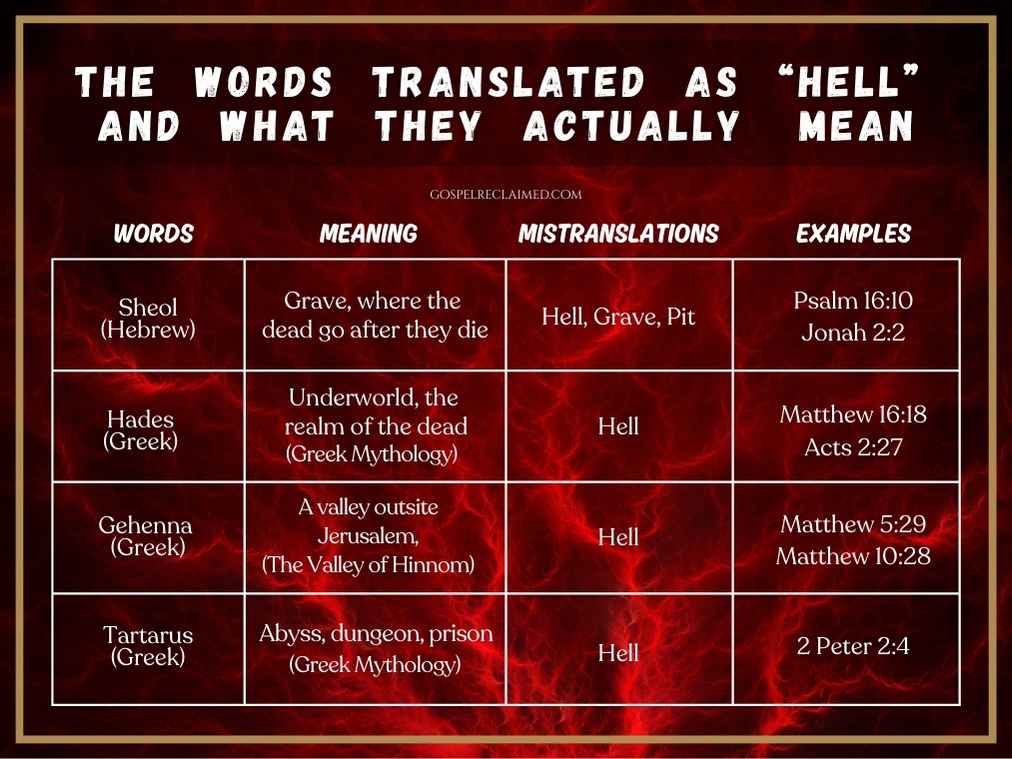

What people now call “hell” was stitched together from four completely different words, each with its own meaning, and none of them describe an eternal torture chamber.

This post pulls back the curtain and lets you meet the real words hiding behind the “hell” mask.

Warning: you might never read your Bible the same way again.

Sheol – Ancient Views of Hell

The Hebrew word Sheol (שְׁאוֹל) appears 65 times in the Old Testament. In the KJV it is inconsistently rendered as “hell” (31×), “grave” (31×), and “pit” (3×); a translation choice many scholars consider misleading.

Long before Jesus, the word Sheol belonged to a much older ancient Near Eastern worldview. In Mesopotamia, Canaan, and surrounding pagan cultures, the dead entered a shadowy underworld — dark, silent, and powerless — where all people went, righteous or wicked.

It was not a place of judgment or torment but the natural destiny of mortal beings, similar to the Sumerian Kur or Babylonian Irkalla, where shades existed in a dim, weakened state.

The early Hebrew imagination mirrored this same understanding.

In Scripture, Sheol is consistently portrayed as: the realm beneath, the silent house of the dead, the destination of patriarchs, prophets, kings, and the wicked alike.

Psalm 89:48 — “What man is he that liveth, and shall not see death? shall he deliver his soul from the hand of the grave (Sheol)?”

Ecclesiastes 9:10 — “… for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave (Sheol), whither thou goest.”

Psalm 6:5 — “For in death there is no remembrance of thee: in the grave (Sheol) who shall give thee thanks?”

It is described with imagery of darkness, stillness, and the absence of activity or praise. Crucially, Sheol was not run by “a devil,” never associated with fire, and never used as a threat of divine torment. To the ancient Israelites, even their most beloved and revered figures acknowledged Sheol as the universal resting place of the dead:

- Jacob stated: “Then shall ye bring down my gray hairs with sorrow to the grave (Sheol).” — Genesis 42:38

- David boldly declared:“If I make my bed in hell (Sheol), behold, thou art there.” — Psalm 139:8

- The psalmist speaking in Racher’s voice wrote: “O LORD, thou hast brought up my soul from the grave (Sheol): thou hast kept me alive, that I should not go down to the pit (Sheol).” — Psalm 30:3

Each of them spoke of Sheol simply as the inevitable place of the dead, not a place of torture, proving that the Hebrews had no concept of a fiery hell. In the mind of ancient Israel, Sheol was simply death’s domain — the place where earthly life ceases, yet always within God’s reach, since He could redeem, raise, and refuse to abandon His beloved to it.

- Psalm 16:10 — “For thou wilt not leave my soul in hell (Sheol); neither wilt thou suffer thine Holy One to see corruption.”

- Psalm 49:15 — “But God will redeem my soul from the power of the grave (Sheol): for he shall receive me.”

- Psalm 30:3 — “O LORD, thou hast brought up my soul from the grave (Sheol): thou hast kept me alive, that I should not go down to the pit.”

If the Israelites never knew of hell as a fiery place of torment for the wicked, then we must ask the honest question: Did Jesus introduce “hell”? Of course not — and we will confirm that next.

Hades – 1st Century Views of “Hell”

The Greek word Hades (ᾅδης) appears 11 times: “hell” (10x ); “grave” (1x) in the New Testament, and in the Septuagint (the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures) it is the standard word used to translate Sheol.

Like Sheol, Hades originally meant the unseen realm of the dead, not a fiery chamber of torment. Yet by the time of Jesus, Jewish beliefs about the underworld had become varied, shaped by centuries of foreign occupation and the cultural atmosphere of the Greco-Roman world.

1. Israel Under Foreign Empires

When Jesus walked through Galilee and Judea, Israel had not been an independent kingdom for centuries. After the Babylonian exile, Judea lived under Persian rule, then under Greek rule after Alexander the Great conquered the region in 332 BC. During the Hellenistic era it passed between the Ptolemies and Seleucids, experienced a brief period of autonomy under the Hasmoneans, and finally fell under Roman control in 63 BC, with Herod the Great as Rome’s client king before Rome took direct control.

This meant that the entire world Jesus inhabited was saturated with Greek and Roman language, philosophy, and religious imagery—including the Greek concept of Hades.

In classical Greek thought, Hades was the abode of the dead beneath the earth, a shadowy realm where both righteous and wicked went. It was ruled not by a devil but by the god Hades or Plouton, a custodian of the dead, not an active tormentor.

By the 1st century, many in the Greco-Roman world envisioned Hades as a temporary underworld where souls waited for some kind of judgment, though the specifics varied widely among Greek authors. Later philosophical writers influenced by Plato increasingly divided Hades into pleasant regions for the virtuous and darker realms for the wicked.

When the Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Greek, the word Hades became the standard translation for Sheol, meaning Jews reading their Scriptures in Greek encountered their own ancient concept through a word already filled with Greek (pagan) afterlife associations.

2. Second Temple Judaism: A Mixed and Evolving Landscape

From roughly the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD—the period of Second Temple Judaism—Jewish views on the afterlife no longer reflected a single shared belief.

Some writings continued to echo the Old Testament’s picture of Sheol as the common, silent destiny of all, without reward or punishment. Other writings, especially apocalyptic texts, described Sheol/Hades as having compartments or regions for the righteous and for the wicked.

A major example comes from 1 Enoch 22, which portrays the spirits of the dead as dwelling in distinct “hollow places,” awaiting a future judgment. This is not the Old Testament view but a later Jewish development under Hellenistic influence.

The Jewish historian Josephus, writing in the 1st century, confirms that different Jewish groups held different beliefs.

- The Pharisees believed souls survived death and would experience rewards or punishments under the earth before resurrection.

- The Sadducees rejected resurrection altogether and believed souls perished with the body.

- The Essenes spoke of good souls living in a gentle place while bad souls were confined to a tempestuous shadowy region—Josephus explicitly says this view resembles Greek philosophy.

This complex landscape matters, because Jesus spoke into this very world. His audience included Pharisees who believed in resurrection and judgment, Sadducees who denied both, apocalyptic thinkers expecting a divided Sheol, and ordinary Jews influenced by Greek ideas simply through language and culture.

By Jesus’ time, it is historically accurate to say that many Jews, especially Pharisees, Essenes, and apocalyptic teachers, viewed Hades as the realm where both righteous and wicked awaited God’s judgment, while others, like the Sadducees, believed death was simply the end.

Hades was increasingly understood not only as the realm of the dead but also as the place from which God would raise and judge the dead, a view empowered by Daniel 12:2.

3. Hades in the New Testament

The New Testament uses Hades in ways that reflect this first-century diversity. Jesus warns Capernaum in Matthew 11:23 and Luke 10:15 that it will be “brought down to Hades,” contrasting exaltation with humiliation, not describing torture.

- In Matthew 16:18, “the gates of Hades shall not prevail” refers to the realm of death itself, not a fiery place of demons.

- Revelation 20:13–14 speaks of death and Hades giving up the dead and then being destroyed. Hades is temporary, defeated, and emptied, not eternal.

Psalm 16:10 in the Septuagint reads:

“You will not abandon my soul in Hades,”

Which Peter quotes in Acts 2 to proclaim the resurrection: Jesus went to Hades, and God raised Him out of it.

In Acts 2:31 Peter repeats: “His soul was not left in Hades.”

None of these mentions of Hades describe an eternal, conscious-torment dungeon.

Jesus Himself descended into this realm:

Revelation 1:18

“I am He that liveth, and was dead; and behold, I am alive forevermore… and I have the keys of Death and Hades.”

What will Jesus do with the keys?

Lock people in forever, or set captives free?

That’s what He Himself said:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he hath anointed me

to preach the good news to the poor;

He hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted,

to preach deliverance to the captives,

and recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty them that are bruised,

to preach the acceptable year of the Lord.” Luke 4:18–19 (

Peter added:

“whom heaven must receive until the times of restoration of all things, which God has spoken by the mouth of all His holy prophets since the world began.” Acts 3:21 (NKJV)

Everything about Christ’s mission points in one direction:

Restoration, not retribution.

Deliverance, not destruction.

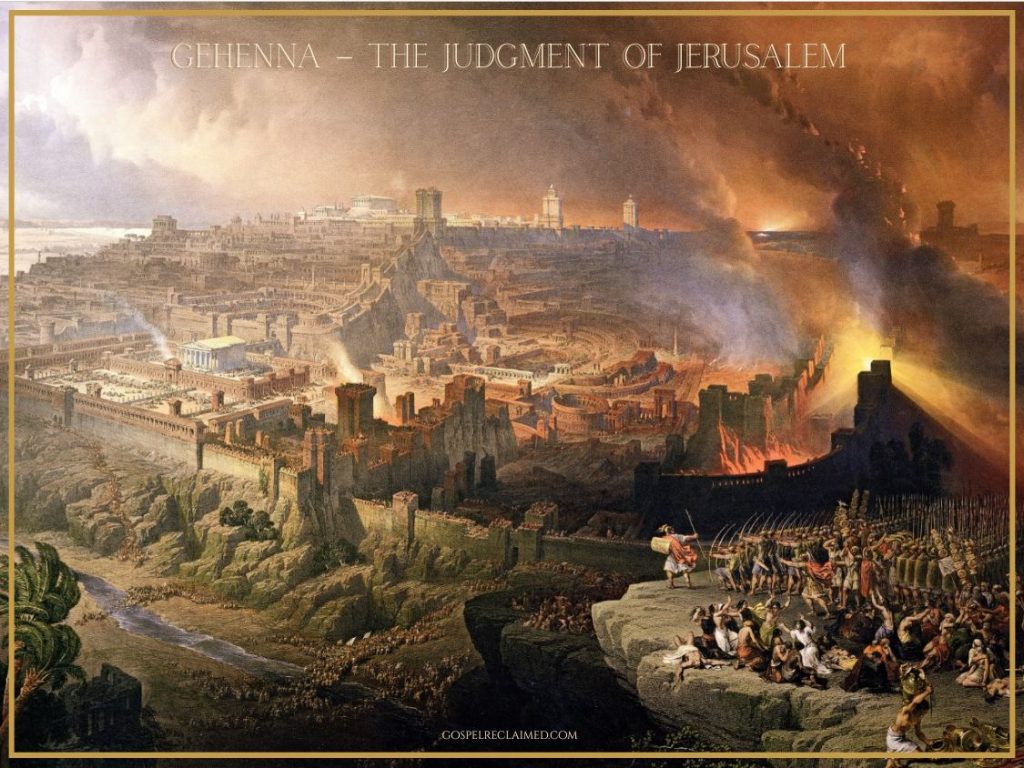

Gehenna — The Judgment of Jerusalem

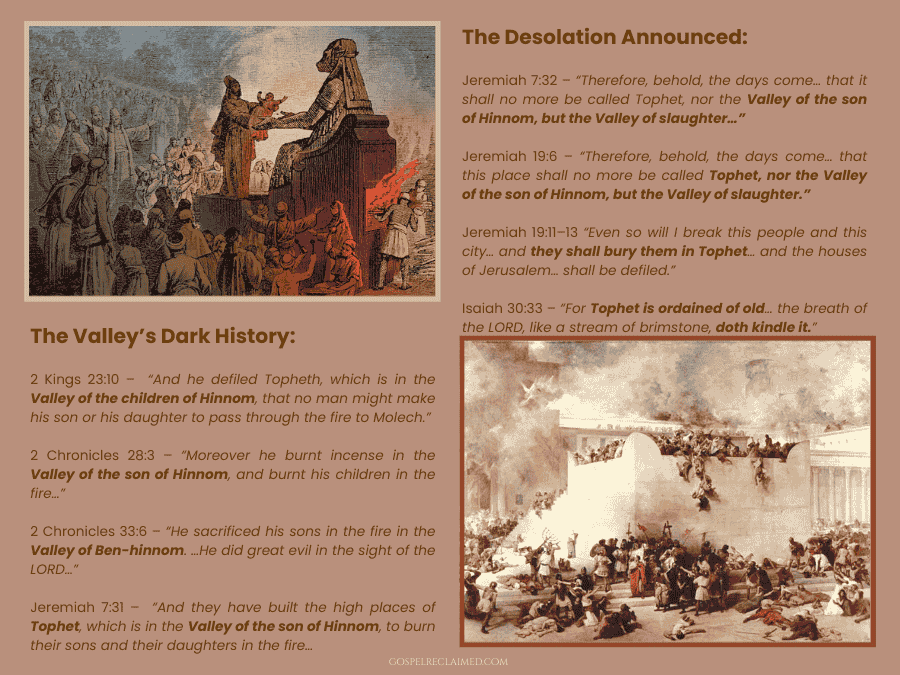

In the Hebrew Scriptures, Ge Hinnom (גֵּי־הִנֹּם — “Valley of Hinnom”) was a real geographical location just south of Jerusalem’s walls. In the New Testament it appears twelve times, translated in the KJV as “hell” (9x) and “hell fire” (3x).

This valley carried a dark memory in Israel’s history: it was the very place where several kings of Judah offered their sons and daughters to Molech, burning them in idolatrous rituals (Jeremiah 7:30–31; 19:2–6). Because of this abomination, the Lord warned that the same valley would become “the Valley of Slaughter,” where the corpses of His people would lie unburied.

That prophecy was fulfilled twice — first when Babylon destroyed Jerusalem in 586 BC, and again when Rome did the same in AD 70.

By Jesus’ time, that valley — Ge Hinnom or Gehenna — had become a symbol of national ruin and judgment for their rebelion in the hands of the Babylonians. The people of Judea knew Jeremiah’s warnings well; they had already seen one destruction and unaware stood on the edge of another.

So when Jesus said, “How will you escape the judgment of Gehenna?” (Matthew 23:33), His audience didn’t picture an other-worldly hell, they pictured that valley south of Jerusalem — the cursed land Jeremiah had named Valley of slaughter

The Greek word for “judgment” here is κρίσεως (kriseōs), from krisis — meaning decision, separation, or distinction. It doesn’t mean divine condemnation; it refers to a decisive outcome — the inevitable result of Israel’s corruption. Jesus was saying, in essence: How will you escape the consequence of the path you’ve chosen?

Paul later wrote, “For he that soweth to his flesh shall of the flesh reap corruption; but he that soweth to the Spirit shall of the Spirit reap life everlasting.” (Galatians 6:8 KJV)

And Hosea had said long before, “They have sown the wind, and they shall reap the whirlwind.” (Hosea 8:7 KJV)

Jesus’ warnings about Gehenna were not a divine curse but a cause-and-effect reality. Israel’s leaders were sowing corruption, violence, and pride— and would soon reap destruction at the hands of Rome. Jeremiah had also warned of the Babylonian invasion:

“Behold, My anger and My fury shall be poured out upon this place… it shall burn, and not be quenched.” (Jeremiah 7:20 KJV)

That fire wasn’t everlasting; it was a national disaster that burned until nothing remained.

Jesus echoed Jeremiah’s imagery — a fire no one could put out once the “kriseōs” began. And in AD 70, His warning came true: Roman legions besieged the city, famine consumed it, the Temple was reduced to ashes, and the valleys filled with bodies, just as Jeremiah had foreseen.

Every time Jesus warned about Gehenna, He was speaking directly to His own generation.

He declared, “These are the days of vengeance, that all things which are written may be fulfilled” (Luke 21:22),

and He prophesied that “there shall not be left here one stone upon another” (Matthew 24:2).

The destruction He spoke of was not a distant, future apocalypse, it was the upcoming judgment upon Jerusalem in their own lifetime, just as He said: “This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.”

And forty years later, it happened. In AD 70, Rome surrounded the city, slaughtered its inhabitants, and burned the Temple to the ground. The “unquenchable fire” consumed everything that could be burned—the Temple system, the old covenant order, and the national pride that resisted God’s call to holiness and mercy.

Sin always destroys from within; judgment in Scripture is often the unveiling of the inevitable consequences already set in motion.

Just as in the Garden of Eden, God did NOT say, “If you disobey, I will punish you forever.”

He warned, “If you do not trust My voice, your own grasping for good and evil will bring death to your soul and body.”

Gehenna’s warnings follow the same pattern: not threats of eternal torment, but prophetic warnings about the tragic self-destruction that comes when the people of God abandon the way of life.

Distinguish The Flames

The Scriptures speak of fire in two very different ways, and confusing them created centuries of false theology.

Gehenna’s fire was literal, first-century destruction fulfilled in AD 70 — a visible, historical event, not a vision of eternal torment.

Baptism with fire is the inward transformation Malachi and John announced:

“For He is like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap… He will purify the sons of Levi.” (Malachi 3:2-3)

“He shall baptize you with the Holy Ghost and with fire.” (Matthew 3:11)

The first fire destroyed a city; the second purifies the soul. Gehenna’s fire ended; the fire of Christ still refines.

Even James used the word symbolically:

“The tongue is a fire, a world of iniquity… and it is set on fire of Gehenna.” (James 3:6) — a description of the corruptive power of the human tongue, not a post-mortem location.

And Jeremiah 19:2–15 reaffirms the valley’s historical curse — Tophet, the Valley of Hinnom (Ben-hinnom), marked as a site of horror for the blood spilled there.

Today, that same valley is no longer cursed or burning. It’s a peaceful green park on Jerusalem’s south side (picture below). You can visit the Valley of Hinnom, sit under a tree, and have a picnic where fires once smoldered. The prophecy is complete; the valley has been restored.

After Jesus’ resurrection, not a single apostle ever warns believers about Gehenna. Paul never mentions it. Peter never mentions it. John never mentions it.

Paul boldly affirmed, “I have not shunned to declare unto you all the counsel of God.” (Acts 20:27) And yet, in all his Spirit-inspired letters, he never once teaches or even mentions Hades or Gehenna.

If Gehenna were truly the eternal destination of billions of souls, wouldn’t the apostles have made it their central warning in every letter? But they never did. Their message was the finished work of Christ, the reconciliation of all things, the new creation in Him, and the transformation that comes from renewed minds, not fear of a valley that had already burned.

Gehenna’s flames belonged to history, not eternity. They marked the end of an age, not the fate of souls. The warning has been fulfilled.

The valley of “unquenchable fire” and “eternal judgment” is green again.

Tartarus — A Hellenistic Image Misread as Eternal Fire

The Greek word Tartarus (Τάρταρος) appears only once in the entire Bible and was unfortunately rendered as hell in the KJV.

Like Hades, Tartarus was never part of ancient Israel’s theology; it was a Greek mythological term that first-century Jews knew because their land had been ruled by Greek empires and was now under Roman authority.

Jewish writers of the era, such as Philo and Josephus, frequently used Greek cosmological vocabulary, reflecting how deeply Hellenistic language had shaped everyday speech and belief, even when those ideas were not rooted in the Hebrew worldview.

1 Enoch 20:2–3 & 21:7–10 (widely read in the 1st century, quoted in Jude) describes a “deep abyss,” “gloom,” and the “prison of the angels.”

Philo, On Dreams 1.22, references souls in the underworld being restrained in a “deep place.”

Josephus, War 2.8.14, describes the Essenes’ belief that wicked souls are confined to a dark, stormy place.

None of these texts treat Tartarus as a human afterlife destination, always as a holding place for rebellious spirits awaiting judgment.

Important note:

According to Jesus and the apostles, the decisive judgment already took place at the cross, where the powers of death, darkness, and the unseen realm were stripped of authority and publicly defeated (John 12:31–32; Colossians 2:14–15; Hebrews 2:14).

When the King James translators rendered Tartarus as “hell” in 2 Peter 2:4, this single mythological reference was pulled out of its historical context and placed into a medieval framework of eternal torment, a translation decision that continues to confuse believers today.

2 Peter 2:4 (KJV) – “For if God spared not the angels that sinned, but cast them down to hell (Τάρταρος)…”

Peter borrowed the Greek concept to describe a temporary prison for disobedient messengers, not a destination for humans, and not an eternal inferno.

This becomes even clearer when we read other passages that speak of the same event.

1 Peter 3:18–20 says that after His death, Jesus went and proclaimed to the spirits in prison — the very ones who disobeyed in the days of Noah.

And Jude 1:6 adds that these angels are kept: “…in eternal chains under gloomy darkness until the judgment of the great day.”

Even though the chains are called eternal, Jude immediately defines the duration: until the day of judgment. This proves Tartarus was temporary, not endless.

This fits perfectly with the larger biblical story:

If death itself is destined to be destroyed (1 Corinthians 15:26), and if Hades will be emptied and abolished (Revelation 20:13–14), then every dark prison faces the same fate.

It is astonishing that later theologians hijacked this ancient Greek term, tore it from its limited mythological context, and built an entire medieval doctrine of eternal conscious torment upon it, a meaning the apostles never gave it.

In short:

Tartarus is not “hell.”

It was not for humans.

It was a temporary spiritual prison from which Jesus Himself proclaimed victory.

What About The Lake of Fire?

The idea that “hell” is the Lake of Fire—eternal, hopeless, and merciless—quickly unravels when we read Scripture with honest eyes and an open heart.

The Bible actually tells a far better story:

A story of purification, not punishment.

A story of love stronger than death.

A story in which God’s fire restores, not destroys.

Still have questions? You should.

What about those intense words in Revelation—“second death,” “torment,” “sulfur,” “eternal fire”?

Spoiler: none of them support eternal conscious torment once you understand the language, culture, and context.

➤ Click here for a deep dive into What the Lake of Fire Really Is.

From Augustine to the Middle Ages: How “Hell” Became a Weapon

The doctrine of eternal conscious torment did not come from Moses, the prophets, Jesus, or the apostles. It grew slowly, century by century, shaped far more by politics, philosophy, and fear than by Scripture.

After the first centuries of the church (where universal restoration was openly taught by many early Fathers), a massive shift occurred. With Augustine in the 4th–5th century, the Western church turned away from the hope of restoration and toward a rigid, punitive view of the afterlife. Augustine rejected the original Greek understanding of aion and aionios (“age,” “age-lasting”), insisting instead on the Latin idea of eternus—a philosophical, not biblical, concept. This became the foundation for the Western doctrine of “eternal hell.”

By the Middle Ages, this new theology had merged with medieval imagination—flames, demons, torture chambers, iron hooks, caverns of despair. None of it came from Scripture; all of it came from the culture. Priests and popes soon discovered how effective fear was in controlling society.

If eternal torment awaited those who disobeyed the Church, then obedience was not just expected—it was mandatory. Fear became a tool of governance. Then Dante arrived.

In The Divine Comedy (1300s), Dante’s Inferno gave Western Christianity its first fully illustrated “hell”—a brutal, violent, sadistic underworld structured in circles of torment. It was brilliant literature but terrible theology. Yet the medieval church embraced it wholeheartedly. For many, Inferno became the lens through which they read the Bible itself.

And so, a doctrine built on mistranslated words (Sheol, Hades, Gehenna, Tartarus), mixed with pagan mythology, shaped by empire, and glorified by medieval poets became the dominant Christian narrative for a millennium.

Not because Scripture taught it.

But because fear controlled people better than love.

This is why the truth matters.

If “hell” as we know it came from Augustine’s Latin philosophy, medieval superstition, and Dante’s imagination—not from the teachings of Jesus—then the entire system collapses under its own weight. The doctrine of eternal torment is the most wicked perversion of the Good News, turning the Father of love into a cosmic torturer and poisoning the Gospel with fear.

If you want to see how this doctrine harmed the world, and why it never belonged to Christianity in the first place, I invite you to read my full post: ➤ Hell – The Most Evil Doctrine of All Time

Rethinking Hell — From Terror to Truth

Hell, as commonly understood today, a place of eternal conscious torment for the lost, is not what Scripture teaches.

Mistranslations and shifting interpretations, especially in the KJV, opened the door for pagan imagery and later medieval fears to reshape a doctrine that had never existed in the mind of ancient Hebrews.

Once these foreign ideas entered theology, they created centuries of confusion, fear, and distorted views of God.

Correcting the language restores a far more hopeful and restorative picture of divine justice.

As we’ve seen, the terrifying images of “hell” many of us inherited were not rooted in the original words of Scripture but in cultural assumptions, mistranslations, and fear-based traditions. Sheol, Hades, Gehenna, and Tartarus, none of them depict endless conscious torment.

Somewhere along the way, the message of God’s restorative love was buried under layers of human misunderstanding, or perhaps became a mirror of the human heart rather than a revelation of God’s.

But if “hell” as eternal torture is a mistranslation…

If the God revealed in Christ is not the destroyer but the Restorer…

Then it raises a bigger, bolder, life-changing question:

What else have I believed that isn’t true?

This is only the beginning.

There is a whole Gospel to reclaim—one that truly sounds like Good News.

Stay curious. Stay bold.

The Good News does not leave loose ends.

FAQs

What does HELL mean?

The word “hell” comes from the Old English hel or helle, rooted in Germanic mythology, and was the name of the Norse goddess Hel, who ruled the underworld—not a biblical concept, but a pagan one later adopted into Christian vocabulary.

What does Gehenna Mean?

In the Hebrew Scriptures, Ge Hinnom (גֵּי־הִנֹּם — “Valley of Hinnom”) was a real valley just south of Jerusalem’s walls. It was there that Judah’s kings offered their sons and daughters to Molech, burning them in idolatrous rituals (Jeremiah 7:30–31; 19:2–6).

What are the words translated as “hell” in the Bible?

Sheol, Hades, Gehenna, and Tartarus—none of them were meant to paint a picture of endless conscious torment.

Somewhere along the way, the message of God’s restorative love was buried beneath the rubble of human misunderstanding, or perhaps, it became a reflection of the human heart, not God’s